The Fight for Tule Elk: Climate Change, Ranching, and the National Parks Service

By Kimia Pourmehr, WELLKIND Forestry Intern

Kimia Pourmehr was an intern for WELLKIND Forestry during our fall 2021 session, exploring the impacts of cattle ranching in Point Reyes and other local environmental issues.

The tule elk is a species native only to California. They live in habitats across the state, ranging from marshlands to grassy coastlines. They are most often seen in the Point Reyes National Seashore, where many tourists travel just to catch a glimpse. However, these majestic animals do not live at ease. They have been sequestered into a small patch of land and deprived of resources. Their prison on the beautiful coastline is killing them.

Ranchers

While ranchers have been in Point Reyes National Seashore since long before the opening of the national park, they weren’t expected to stick around. In 1962, when the national park was established, it was agreed that ranchers would have 20 years to relocate their farms in an effort to protect the land. In this time, significantly more farms had moved into Point Reyes, and when 20 years were up, ranchers had one small request. They wanted just five more years. But five years later, they had the same request, and so the cycle began. Today, 17 ranches still inhabit 38,000 acres of the national park. Even after successive NPS payments totaling over $360 million in today’s dollars, they have no intention of moving anytime soon.

My Trip To Point Reyes

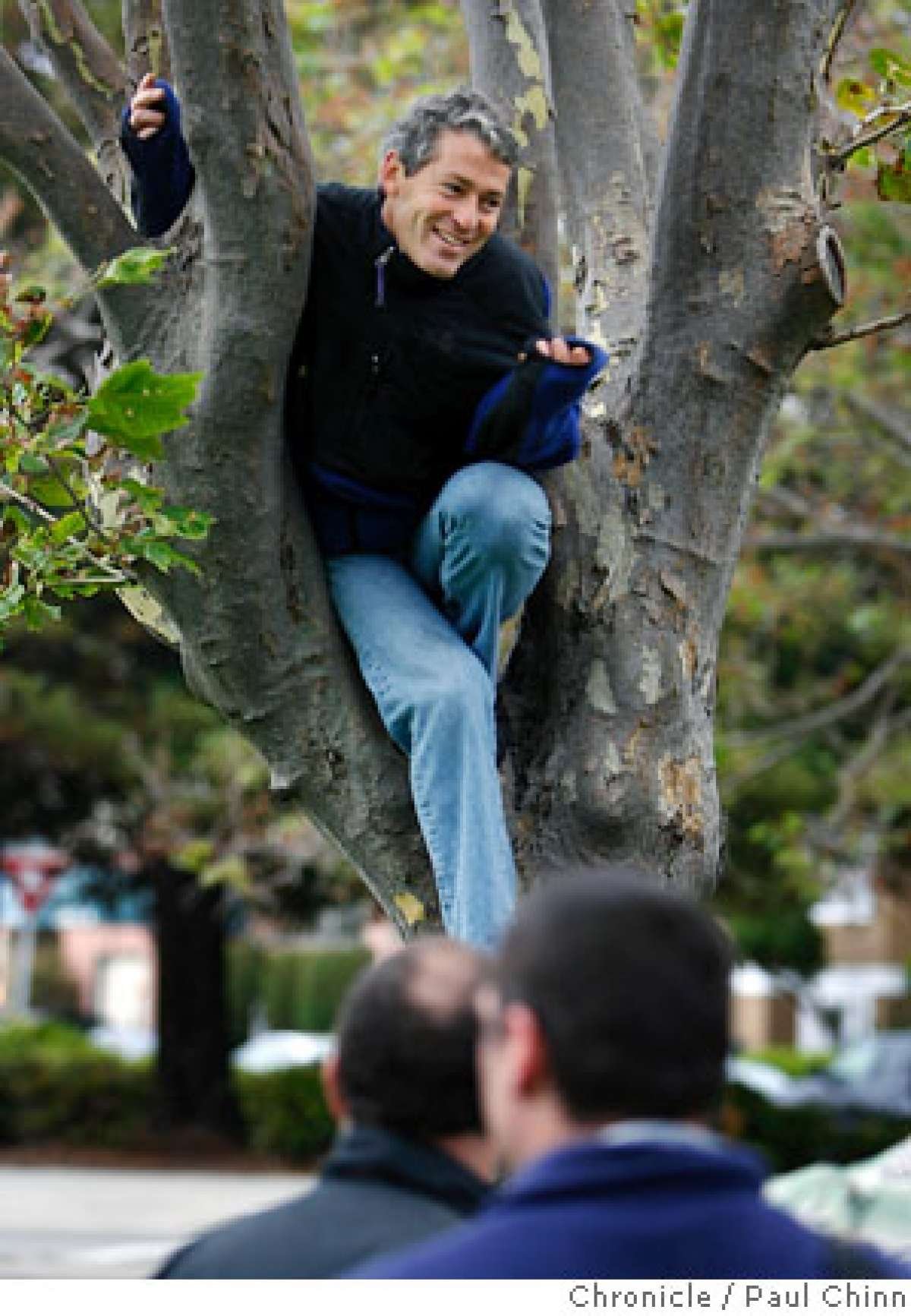

I got the chance to visit the tule elk and experience first-hand the extent of farmland in the park and the damage it has done to biodiversity. I came to Point Reyes with Jack Gescheidt, an environmental activist. Jack has been involved with the tule elk on multiple fronts, organizing protests, writing letters to politicians, heading lawsuits, and publishing articles. He explained to the interns about how the elk have been suffering from the historic California drought. In the past year, he has been pushing for the national park to provide supplemental water to the elk. When they refused, troughs were brought in and hundreds of protesters hiked in water to fill the troughs and provide at least some water.

While we drove through the ranch lands, Jack showed us how the cattle have decimated the land, leaving only a stubble of non-native grass in the fields cut short by the cows. The rolling hills were clear of any brush and very few trees. Nearby waterways are dirty with infected feces that spread coliform bacteria. Their ranchers don't have any smaller of a footprint. They dump trash on public land, leave old cars to rust away, and pile old farming equipment onto the land that was once dominated by protected wildlife.

As we approached the tule elk “reserve,” you could clearly see the difference where beautiful scrub-land dominated and the muddy pasture from the cows on the other side of the fence. It was a stark difference, and it was clear that the elk side of the fence supported a multitude of animals in a healthy—but enclosed—ecosystem.

While many other animals have struggled during the drought, the tule elk have had more issues because of the fence that traps them. Tule elk are not unfamiliar with traveling with their herds to find food or water resources, but the 2,000 acres of the national park is far from enough space for a healthy population of elk. They are fenced into the small space, with no room to move. During the drought, their water sources dried up and the fence prevented them from moving.

Right outside their fence, cattle have a free range of 38,000 acres. They drink up to 30,000 gallons of water a day, while the elk scratch dry ground to no avail. For the elk, stepping past the fence, if they are even able to get over, it could mean death. The ranchers will shoot any elk coming onto their property. With scarce water sources and the National Park Service refusing to provide water, 150 elk died during the recent drought.

Conclusion

This drought has highlighted how climate change will continue to imperil the elk, and that the National Park Service needs to step up in elk preservation. The tule elk in Point Reyes will not thrive unless they are able to roam freely. The cattle never belonged in a national park, and now is the time for them to leave. If not, our endemic species will be lost forever and our national park will become a barren wasteland.